Debt to Income ratios (DTIs) are a new concept for New Zealand mortgage markets. A Debt to Income ratio measures the proportion of a borrower’s income that goes towards servicing debt and is often used by lenders to assess the creditworthiness of potential borrowers. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand in 2021 initiated consultation on the implementation of DTIs as a prudential control – similar to Loan-to-Value (LVR) ratios – used to manage macro risks to financial stability by imposing restrictions on how much people could borrow; and in January they announced that DTI limits will likely come into force later this year.

In this blog post, we’ll delve into what DTI ratios are, explore examples from countries that have implemented them, and examine the effects on local property markets and access to credit, especially for lower-income households.

What is a Debt to Income Ratio?

A Debt to Income ratio is calculated by dividing a borrower’s total debt by their gross income. It is expressed as a ratio: for example, if a household earns $100,000 per year and has total mortgage debt of $500,000, their DTI ratio would be 5:1. Lenders will be required to assess this ratio for new borrowers, and will have limited in the amount of lending they can make at ratios above a certain level.

What is being proposed in New Zealand?

The specific ratios that the RBNZ is proposing are:

A DTI of 6:1 for owner occupiers. For example, the maximum a household with a $100,00 annual income would be able to borrow would be 600,000. The proposal limits banks to lending above this level at a maximum of 20% of their loan book.

A DTI of 7 is proposed for property investors; again with a maximum of 20% of a banks loan book above this level.

In conjunction with Debt to Income limits, the RBNZ is proposing to reduce the use of Loan to Value ratios (LVRs) as a prudential control. Currently, most mortgage lending in new Zealand must be made with a loan to value ratio of less than 80%, which has been a perennial problem for first home buyers – saving a 20% deposit can be a real challenge for many. The LVR restrictions would remain at 80% for owners, but the level of lending permitted by banks above these levels would increase from 15% to 20%. And for investors the LVR limit would increase from 65 to 70%, with a max level of lending by banks above this of 5%.

How do DTI’s Affect Property Markets?

Impact on Property Markets

DTI ratios can have an influence on overall property prices. By capping how much individuals can borrow relative to their income, these measures can cool down overheated markets and over time, this can help stabilise property prices and reduce the risk of a housing bubbles. However, strict DTI limits can also slow down market activity and may lead to a short-term decrease in property prices. The RBNZs goals with introduction of DTIs in New Zealand is more about financial system stability; that is, keeping limits on the number of borrowers at the limit of their servicing capacity and more susceptible to loan defaults if interest rates increase or incomes reduce, and reducing the likelihood of property price bubbles.

Access to Credit for Lower-Income Households

One of the criticisms of DTI ratios is their impact on lower-income households. These ratios can disproportionately affect these households as they tend to have higher DTI ratios due to lower incomes. Strict limits can make it challenging for them to access mortgage financing, thus impacting their ability to own homes, particularly first home buyers who are already dealing with high property prices and competition from investors.

What about New Zealand specifically?

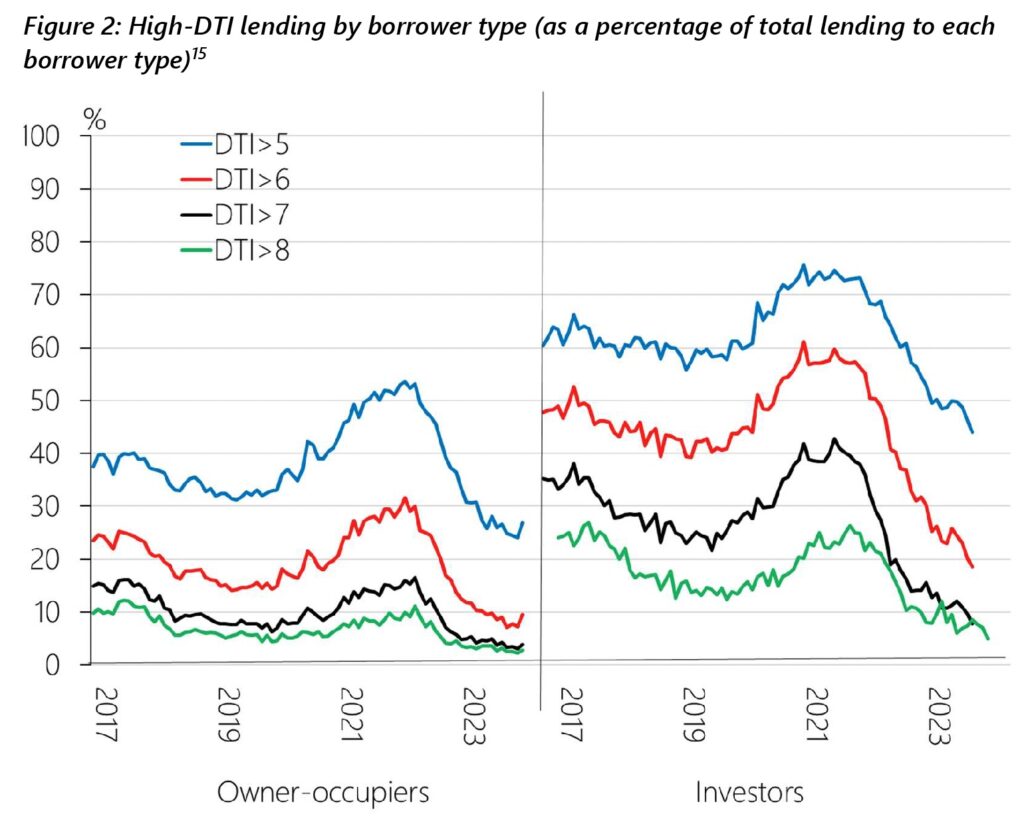

The following chart is taken from the RBNZ consultation paper on Debt to Income ratios and shows how lending at various DTI levels has varied over the last 8 years:

For owner occupiers, the red line is the proposed limit and for investors the black line is the proposed limit. As of early 2024, around 10% of mortgage lending is made at a DTI above 6, which effectively means that if introduced today, DTIs for owner occupiers would make no different to lending. A DTI of 6 would have been restrictive in the 2021-2022 housing price bubble, where lending at 6 or above was more than 20% of new mortgage lending. This helps illustrate how DTI’s can help reduce the severity of price bubbles – and the situation is similar for investors, with the percentage of bank lending to investors at a DTI of 7 or higher currently well under the 20% limit.

In summary – assuming that not much changes in the next few months, it’s unlikely that DTI restrictions will have a material impact on borrowers access to credit or housing prices on their own.

DTIs in other property markets

Various markets around the world have imposed restrictions on high Debt to Income ratio lending, or have guidelines in place regarding bank credit policy. Some examples include:

Australia

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), which oversees banks in Australia, has been closely monitoring household debt levels. In response to rising house prices and household debt, APRA has set guidelines for banks to limit the number of loans that can be given out at high DTI ratios, though it hasn’t set an explicit cap.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom introduced DTI limits in 2014. The Bank of England placed a cap where no more than 15% of new mortgages could have DTIs higher than 4.5. This move was aimed at cooling down an overheated housing market and preventing borrowers from taking on excessive debt.

South Korea

South Korea has actively used DTI ratios to stabilise its housing market. The government adjusts DTI limits according to the economic climate and housing market conditions. This dynamic approach helps to moderate housing prices and ensures that borrowers are not exposed to high debt levels.

Canada

The Bank of Canada has been proactive in managing the risk of household debt. While it hasn’t directly imposed DTI limits, it has implemented measures like stress tests for mortgage borrowers. These tests require potential borrowers to qualify at interest rates higher than the actual rate for their mortgage, effectively limiting how much they can borrow relative to their income.

Ireland

The Central Bank of Ireland introduced DTI limits in 2015. These measures were part of a broader set of macroprudential rules aimed at securing the banking sector and the economy. Borrowers are generally limited to borrowing 3.5 times their gross annual income – significantly more restrictive than New Zealand’s proposal – a move that has been significant in stabilising the Irish housing market after its dramatic crash in 2008.

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, mortgage lending is regulated with a focus on income criteria. The DTI ratio is an essential part of the mortgage assessment, with limits set on how much individuals can borrow based on their income, ensuring that debts remain manageable.

What next?

Assuming nothing changes in the next few months, introduction of Debt to Income ratios seems to be a relative certainty. At current house price levels, this is likely have limited impact in the short term – where they may start to play a role is if house prices suddenly inflate rapidly in relation to median incomes. In this situation, it’s the marginal borrowers – such as lower-income and first home buyers – that are more likely to be restricted first. And watch for banks to price high-DTI lending at a premium – in the same way that high loan to value ration borrowers today lose access to premium rate offers or pay low-LVR fees, banks may choose to impose additional cost on more marginal borrowers.

As always, if you have any questions regarding mortgage lending or property investment, please reach out to us.

Ready to get in touch?

Get in touch now for a free no-obligation chat about how we can support you and your investment needs.